A few weeks ago around lunchtime, more than 100 journalists at The Wall Street Journal staged a walkout, an hour-long protest that culminated outside of editor in chief Emma Tucker’s office. Angered by yet another round of layoffs—the latest of which hit a handful of people on the US News team earlier that day—and fed up with stalled contract negotiations, members of the union decorated Tucker’s glass walls with their discontent. Staffers took turns sticking Post-its, scrawled with messages like “EXPLAIN YOURSELVES” and “The cuts are killing morale,” to the exterior of the office, navigating around Tucker’s executive assistant, who was standing guard in front of the door. “Do you think this is helpful? Are you going to stick them on me?” she asked, scolding staffers for being impolite and eventually, as a sea of fluorescent-colored squares amassed, calling security. The episode was over a few minutes later, with nary a sticky note in sight by the time Tucker, who’d been absent for the whole fiasco, returned to her office.

When I stopped by the Journal a week later, Tucker seemed unfazed by the turmoil. “I would expect morale to be low because if you’re changing things, that’s normal,” she told me. “But I would also dispute that all morale is low,” she added. “The people we’ve promoted—and there have been very many people that we’ve promoted—I don’t think their morale is low.”

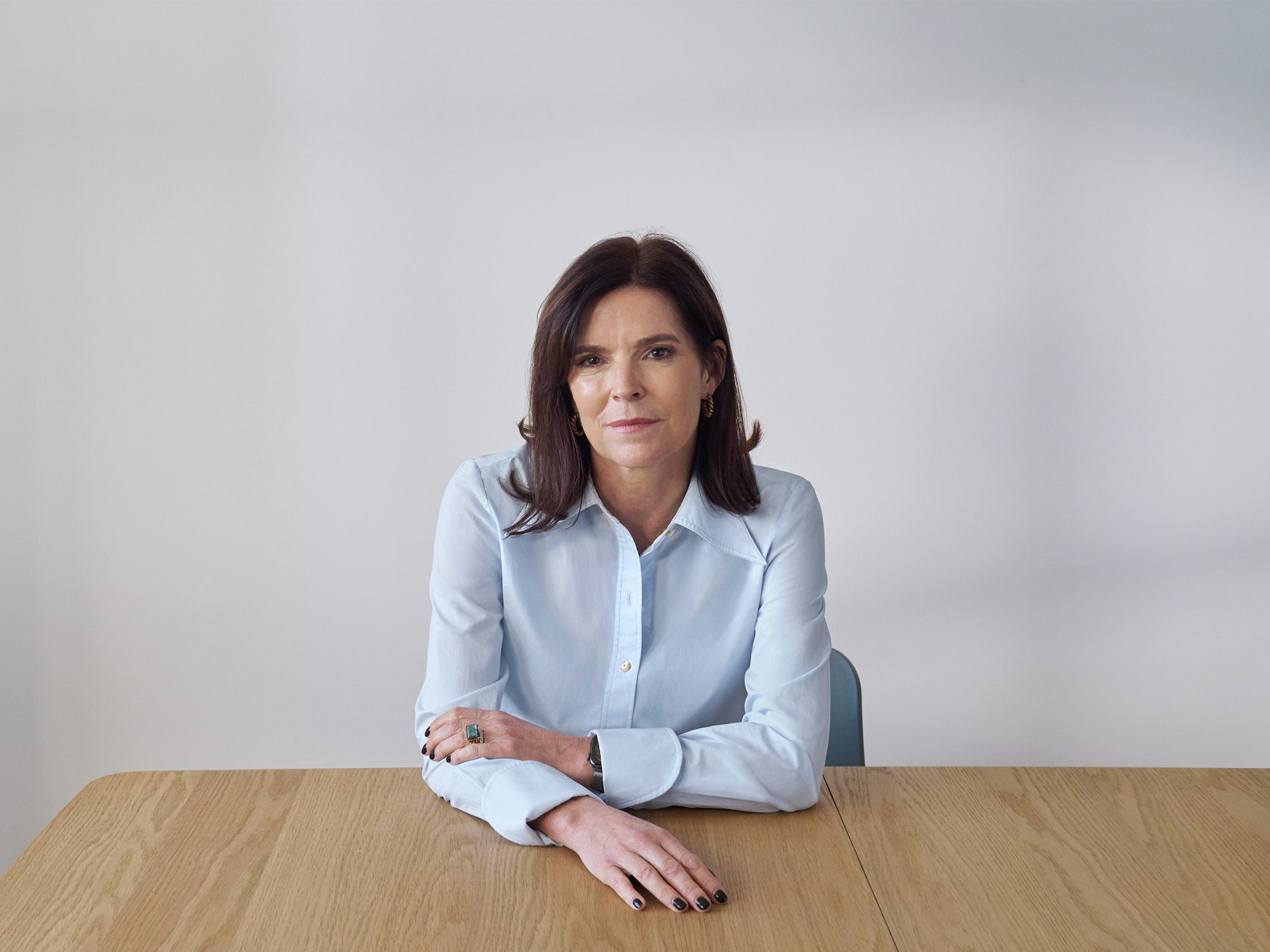

Tucker, a personable and somewhat irreverent Brit, took over the Journal in February 2023. In a little over a year, the 57-year-old journalist has brought color, voice, and a renewed metabolism to America’s business newspaper of record. Sure, you’ll still find stories about interest-rate cuts and investment income. But you’ll also find investigations into Elon Musk’s unusual relationships with women at SpaceX and drug use, the succession battle for the luxury empire LVMH, and messages that Hamas military leader Yahya Sinwar sent to compatriots and mediators. (An attorney for Musk told WSJ that he’s never failed a drug test at SpaceX.) Tucker’s goal is to make the paper “audience-first” and “to grow and retain subscribers,” she told me. It might not sound like the most visionary mission. But the Journal today is, well, better—a more compelling product that a wider swath of people might pick up and read.

“The problem a lot of people face with the Journal is they don’t think of the Journal as for them—that it’s for a very small subset of people on Wall Street,” one senior Journal editor told me. “She has a broader view of what makes something a Journal story.” Tucker’s approach seems to be working: Dow Jones, the publisher of the Journal, recently announced record-breaking digital subscription numbers, with digital subscriptions for its properties—which also include Barron’s and MarketWatch—achieving the largest rate of sequential growth to date.

Upon arriving at the paper, Tucker quickly replaced the old guard with her own people, addressed legitimate editing bottlenecks, and pushed for sharper, more ambitious stories. Staff were generally on board, until she started firing a bunch of their colleagues, with the Washington DC bureau hit especially hard. Some are still Tucker fans, seeing her as the kind of change agent necessary to shake up the Journal, a place mired in vestigial structures and traditions. But she’s lost large pockets of the newsroom in the process of “restructuring,” an effort that, to staff, has largely manifested in pushing out well-regarded editors and esteemed reporters. With no end in sight and little consolation or explanation from Tucker, the newsroom is on edge. “From the outside, it feels like she’s moving incredibly quickly, with sort of summary executions,” an editor from a rival news organization told me. “But from the inside, this has been going on for so long that everyone is in a panic because they don’t know the next person who’ll be taken out and shot.”

It’s a culture shock for a newsroom where people tend to stay 10, 20, 30 years, and whose culture is built upon collegiality and institutional knowledge. It is a place particularly averse to change. Under Tucker, Journal staffers are waking up to something that looks more like the UK’s Fleet Street model: take it or leave it, and fuck you if you don’t like it. Reorganizations are a fact of life in British newsrooms; Tucker, who’s never worked at an American newspaper before now, may have underestimated the culture gap.

Over the course of reporting, I spoke with more than two dozen current and former Journal staffers, whose opinions of the paper’s new editor run the gamut from savior to villain. “She’s a bit of a Daenerys Targaryen, where it was all optimistic. She was a hero freeing us from pronouns and attributions. But now we’ve realized she was put here to slash the Journal down to size and turn us into a metrics-obsessed, subscriber-obsessed, churn-reduction factory,” said one current reporter. Said another: “She may be improving the journalism, while seriously hurting the journalists.”

“There’s no point in me setting out a vision and then going, ‘But we’re just going to carry on doing everything we’ve done before,’” Tucker said. “Everyone said when I got here, We’ve got to change, we’ve got to change. But I’m not naive. I know that everyone says that until it affects them, and then they don’t like it so much.”

Staffers in the Journal’s DC bureau had been anticipating cuts for months; in October, bureau chief Paul Beckett was reassigned, allegedly because he refused to implement them. They were not, however, expecting a “red wedding,” as one staffer described the events of February 1, which was when managing editor Liz Harris, Tucker’s No. 2, went down to the nation’s capital to announce a restructuring of the Washington bureau.

News of the layoffs—which had leaked to other outlets in the days prior—came at 9 a.m., when Harris sent an email inviting the bureau to a conference room for a meeting set to last only 10 minutes. There, Harris, flanked by three other suits, read the news of the reorganization from a piece of paper, but staffers struggled to hear over the wail of a nearby motorcade. “Speak up!” they shouted. Harris kept talking over the noise, telling staff that those impacted would “receive an invitation to meet with us individually today.” She didn’t take any questions. Later, staff watched colleagues get up one by one to meet with HR. By the end of the day, at least 30 staffers were gone; some were told they could apply for other positions. People were crying in the newsroom. Tucker and her team were seen as oblivious to what damage they’d caused, and clueless about how they could’ve done this better.

“Any job loss is bad for the people involved. But at the end of the day, the net total of jobs that we closed in DC was 16, and there were over 90 people in that office,” Tucker said. “We created a bunch of new jobs, as well,” she added. “It wasn’t just slash and burn.”

Tucker said she doesn’t regret not going to DC to do the layoffs herself that day, noting she came a few days later to take questions and welcome new bureau chief Damian Paletta, a former Journal reporter who’d spent the past few years at The Washington Post. Paletta by that time was already trying to re-recruit some of the reporters who’d been fired a few days earlier, including Brody Mullins, who had won a Pulitzer for the paper a year earlier; Ted Mann, who broke the Bridgegate story; and Julie Bykowicz, who chronicled money and influence in Washington. Paletta made personal appeals to all three, asking them to reapply to new jobs at the paper, but they all declined. “Yes, there’s bitterness, but it’s also purely financial—that’s where the handling of the layoffs didn’t seem thought through,” Mullins told me, noting his severance was essentially a full year’s salary. “You’re paying me to leave, but asking me to come back,” as he put it.

(The union has since filed two grievances alleging the paper violated “a job-security provision of the contract by retaining two employees out of seniority order and trying to re-hire three other employees”—Mullins, Mann, and Bykowicz—“in violation of seniority rules,” as Playbook reported. Dow Jones responded to the outlet, saying they “believe the company’s actions were entirely consistent with the provisions of the parties’ labor contract.”)

The layoffs kept coming: later in February, the Journal quietly laid off five international reporters. The following month the paper gutted its standards and ethics team, the group responsible for reviewing sensitive stories prior to publication. Many saw a rethinking of the standards process as warranted: The team could be inefficient and “conservative to a fault,” as one former reporter put it. To old-timers, though, the level of line editing and verification that happened in standards was part of what made the Journal unique.

Standards was part of a broader problem that Tucker heard about early on during her newsroom listening tour, where the most common theme was “we get in the way of ourselves,” she said. “Lots and lots of editing layers, cumbersome structures, silos,” all of which had, over the years, been “slowing things down or stopping people from doing their best work.” These are long-running issues at the Journal, some even predating Rupert Murdoch, who in 2008, a year after purchasing the paper, expressed amazement that Journal stories were touched “an average of 8.3 times” before appearing in print. “The Journal’s very successful, and if something’s successful, there’s a tendency to not want to upset the apple cart,” Tucker said, when I asked her why she thinks her predecessors didn’t make these changes earlier. “I want to make sure that we do this in our time, not with our backs against the wall.”

Eleven more people, largely on video and social media teams, were fired in April. And in May, at least eight reporters on the US News team—which covers breaking and national news—were laid off, cuts that Tucker explained in a memo to staff as part of the paper’s increased focus “on areas where we can best do distinctive work” and shift away from regional and local general news. “There’s a callousness to this sort of drip-drip-drip of firings,” one staffer said. “It’s been asked point-blank, ‘Is there an end in sight? What is that end? Can we get an idea of the timeline on this?’ And there hasn’t been a real answer to that question in any comprehensive way.” Tucker was similarly noncommittal when I asked her whether she’s done with layoffs. “You could never say that, because it would be dishonest. The needs of a newsroom change,” she said. “But I’d say we’re getting close to the structure that I need to support the vision.”

Tucker suggested, “It’s important to keep it in perspective: we haven’t done mass layoffs.” The issue people have with her seems not to be the number of people fired, but her lack of bedside manner while carrying out the whole restructure. “She walked into a newsroom that was pretty excited and welcoming—a newsroom that, frankly, was pretty thrilled to have a woman at the top,” a former Journal reporter told me. “Everyone liked what she was saying. Everyone liked her goals. It’s just that the way she’s gone about doing it has decimated trust in management and is sending so much institutional knowledge out the door, either because people are being laid off or leaving because they fear they’re going to be next. It’s just no way to run a newsroom. People shouldn't go to work every day worried that they’re going to lose their jobs.”

The manner in which she’s ushering in a new era, Tucker said, “may look callous, but it’s so that we get it right, so I don’t have to do it over again.” For those who see the need for urgent change, the recent upheaval at a competitor serves as a cautionary tale. “The dramatic changes at The Washington Post weren’t made and they got to a crisis situation. Emma's doing the gutsy things that are desperately needed,” a Journal editor told me. “We have to be proactive on the front end or we’ll end up being reactive when things are out of our control.”

At a moment when newspapers across the country have seen mass layoffs and even full-scale closures, publisher Dow Jones is in growth mode. In the past four years, it has doubled its digital subscription base and reached five million paying digital subscribers for the first time in May. Also in May, News Corp said its profitability rose slightly as compared to the prior year. Tucker attributes the growth in subscriptions to a reduced churn rate—“there’s no point filling up the funnel if the bucket is leaking out,” as she put it—as well the Journal offering readers more compelling stories. Subscribing to the Journal isn’t cheap. An online-only annual subscription will run you $507, far more than that of The Washington Post ($120 annually) or even The New York Times’ bundle ($300 a year for news and other lifestyle products). “People are coming back to us, and I think it’s because we’re thinking more carefully about how we tell the stories. We’re selling them better; we’re writing them better,” she said.

“Each time that there is a significant shift in the world—or you could call it a major news event—we see a larger number of subscribers come to us,” Dow Jones CEO and Journal Publisher Almar Latour said in an interview. Over the past few years, they’ve seen a larger influx of people willing to pay not only for Dow Jones publications like the Journal or Barron’s but also their B2B services, like Factiva (a news archive service) and OPIS (energy commodity pricing, news, and analysis). “We offer reliable, trusted information,” said Latour, “and I think the market for that in the broader business world is enormous.”

Tucker grew up in Lewes, a Sussex town some two hours south of London. She came to America for the first time at 16, on a scholarship to a school in New Mexico. Then, after a year living in South America, she returned to England, attending Oxford and editing the student magazine there. (“Embarrassingly, it’s called The Isis—the name of one of the rivers in Oxford,” Tucker told me. “It’s slightly awks now.”) After Oxford, she joined the Financial Times as a graduate trainee—along with Rachel Johnson, a journalist and the sister of former prime minister Boris Johnson, who would become a close friend. Tucker stayed in the UK for a few years, covering economics for FT, before going to work abroad for the paper in the late ’90s: first to Brussels for six years, and then to Berlin for three.

“Along the way, I acquired three children,” said Tucker. “By the time I got back to London, I wanted to move away from being a reporter. It was so difficult with the three boys.” (Tucker also has three stepsons with her second husband, whom she married in 2008. “The stepsons I didn’t acquire ’till a bit later—but it’s an entourage, I can tell you,” she adds.) In Brussels, she met Robert Thomson, who was then the FT’s foreign news editor. “It was good fun. He had a real kind of eye for unusual stories, and I was very much up for that,” said Tucker.

After returning back to London, Tucker spent a few more years at FT, eventually overseeing FT Weekend. But after 16 years at the paper, she was getting itchy, and decided to go to The Times of London, Murdoch’s center-right paper, to which Murdoch had already hired her friend Thomson as editor. Tucker and Thomson only overlapped for a year at the Times, because in December 2007 Murdoch had a new paper for him to run. Thomson—who, like Murdoch, is Australian—was named publisher of the Journal and, not long after, its editor. Tucker, meanwhile, stayed at The Times for seven years, rising to the role of deputy editor. Then, in 2020, she became editor of its sister paper, The Sunday Times, which is where she worked until Thomson came calling once again. “It was Almar that hired me,” Tucker said, but “Robert was the first person to sort of broach it.”

She replaced Matt Murray, who, by the end, the newsroom had mixed feelings about. A Dow Jones lifer, Murray was seen as a competent if aloof leader, who steered the newsroom through the pandemic, 2020 election, and various Trump crises fairly well, but alienated some with his micromanaging tendencies. Tucker was an ideal candidate in that she was already a known and trusted quantity inside the broader News Corp universe, yet was also enough of an outsider to not only recognize where change was needed but to execute the overhaul. (Murray, meanwhile, was recently brought in to steer The Washington Post in the wake of a newsroom shake-up.)

Tucker, who succeeded Murray in February 2023, was only a few weeks into the job when Evan Gershkovich, a foreign correspondent for the Journal who had been reporting in Russia, was arrested by Russian authorities on bogus espionage charges that he, the Journal, and the US government vehemently deny. (Last week, Gershkovich’s secret trial got under way.) Tucker immediately appeared all over television to get the word out about Gershkovich and advocate for first-amendment rights. “It actually gets harder, because in those first few weeks, I think we all thought—I certainly thought—Well, this is going to get resolved. He’s an American journalist. He works at The Wall Street Journal. We will sort this,” Tucker told me. “In the moment, adrenaline kicks in and you do what you’ve got to do. Afterwards, when it’s all calmed down, you’re like, Oh god, they’re not about to let him out. And that is hard.”

Staff think Tucker has done right by Gershkovich, keeping his name in the news and encouraging them to do the same. “Ingrained in all of us at the Journal is to be pretty buttoned up, and here came this Evan situation, and she was basically enlisting all of our voices to make sure this topic of conversation didn’t go away and letting us be activists on this one point,” one senior editor said.

Tucker said she didn’t have a mandate coming in, or any explicit orders from the paper’s owner. She speaks only “occasionally” with Murdoch, she said, noting that he “never interferes with what we’re doing.”

“No one sat me down and said, this is what we want,” she said. “My view was, Okay, I’ve got this amazing newsroom full of all these talented reporters…. What can I do to safeguard what we’ve got, but also make sure that we not just survive but thrive in the future?” The industry, she notes, “is facing real disruption,” pointing to the threat of AI and dramatic drops in referral traffic.

Her immediate changes were “fairly cosmetic,” she said. “I felt there was a lot of clutter in the way we presented stories in the text,” she said, getting rid of corporate designations like Inc. and Ltd., and courtesy titles like Mr. and Ms. Then she tried to figure out what people wanted most from the paper, which, according to a monthslong content review, is the Journal’s core content: business, finance, economics, and geopolitics. People who come for the core, she said, stick around longer than those who come for a Style article. Tucker wants to lean into the Journal’s niche—“We are not a lifestyle publication,” she insisted—but to do so in a distinctive way, focusing less on commodity news or incremental stories, and more on exclusives and enterprise-style pieces—and with speed. “There’s no point in us writing a brilliant piece three weeks after something happened,” she said. “We need to be there, part of the conversation, when it’s happening.”

The Journal is indeed nimbler under Tucker, such as with its bombshell investigation into Angela Chao, the global shipping executive and sister-in-law to Mitch McConnell, who died in February on a remote Texas ranch; she was found in her car submerged in a pond. A few weeks later, a Texas sheriff’s office said the death was under “criminal investigation”—a development that caught the eye of Christopher Stewart, an editor on the investigations team. Stewart brought it up during an ideas meeting, where Tucker noted she had been at a dinner the night before with various finance types, some of whom knew Chao and her husband and were talking about the accident. At that point, rumors were swirling about what had happened. The Journal scrambled an all-female team of reporters to get to the bottom of it, revealing, a few days later, that Chao had died after accidentally putting her Tesla in reverse, along with searing details from her final hours. A few days later, the Journal had an article on what to do if your car is submerged in water.

Tucker is focused on making the paper more oriented toward what the audience needs and wants. To better understand reader behavior, Tucker has instituted a new backend data system, where story performance and engagement are ranked across various categories, such as how many clicks from subscribers, how long subscribers spent engaging, new audience reach, and conversions. (There’s also a “missed opportunity” category: high subscriber interest, but low engagement time.)

The dashboards are “not there to tell us what to do,” said Tucker. “If there’s a Wall Street Journal angle on anything, we’ll write about it. But what the dashboards help us with is understanding how we write about stories,” she said, adding, “And frankly, it would be really embarrassing if I was sitting here saying to you, Oh, we’re not using data, we’re just making it up as we go along.”

Take coverage of the gambling industry and the changing regulations around it. “Weirdly, whenever you write about gambling—and I found this actually in my old job—it’s a subject that people aren’t interested in,” said Tucker. Then the Journal tried telling the story through the prism of a psychiatrist who became addicted to online gambling. “The engagement on that piece was as high as it gets,” Tucker said.

Some Journal staffers flinch at Tucker’s obsession with metrics. In monthly meetings early on, “she talked a lot about engagement, or whatever the euphemism for clicks was at the moment,” a former reporter said. “She didn’t talk a lot about what constitutes a good story or speak the language of reporting at all. That was increasingly a warning sign.” Said another former Journal staffer: “It’s a business, I get it. But there is a more noble vision of the profession that motivates a lot of people,” a public-service component that Tucker doesn’t seem focused on.

“One of the best things about being here is this kind of sense in America of how important the fourth estate is,” Tucker said. “And it’s not that it doesn’t matter elsewhere, it does, but it’s really in your DNA. And that’s been great. What I say is, Yes, it does matter, but then we have to make sure it survives,” she continues. “If we all just sit here doing what we’ve always done, one day we’ll wake up and the whole flipping thing will have gone, and we will be like the horse-and-cart makers at the turn of the century who ignored the motorcar.”

She added: “We’re a business publication; we write about these companies all the time. The corporate landscape is littered with companies that didn’t make the changes they needed to make. So I’m just like, Let’s do it now.”

More Great Stories From Vanity Fair

Inside Kamala Harris’s Loyal Circle of Hollywood Friends

Peter Thiel, J.D. Vance, and the Dangerous Dance of the New Right

The Untold Stories of Humphrey Bogart’s Volatile Life

The Truth About Meghan, Harry, and Their California Dream

Inside California’s Freedom-Loving, Bible-Thumping Hub of Hard Tech

The Best TV Shows of 2024, So Far

Listen Now: VF’s Still Watching Podcast Dissects House of the Dragon